Illustration: Yoshi Sodeoka for Bloomberg Businessweek

Businessweek | The Big Take

US military operators started out skeptical about AI, but now they are the ones developing and using Project Maven to identify targets on the battlefield.

By Katrina Manson

Illustrations by Yoshi Sodeoka

February 28, 2024 at 7:00 PM EST

On a summer evening in 2020 at Fort Liberty, a sprawling US Army installation in North Carolina, soldiers from the 18th Airborne Corps pored over satellite images on the computers in their command post. They weren’t the only ones looking. Moments earlier, an artificial intelligence program had scanned the pictures, with instructions to identify and suggest targets.

The program asked the human minders to confirm its selection: a decommissioned tank. After they decided the AI had it right, the system sent a message to an M142 Himars—or High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, the wheeled rocket launcher that’s a mainstay of America’s artillery forces—instructing it to fire. A rocket whistled through the air and found its mark, destroying the tank.

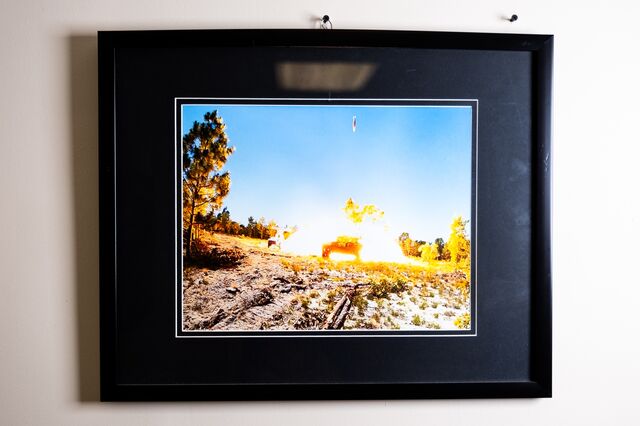

The explosion was unlike any other in the hundreds of live-fire exercises that occur each year on Fort Liberty’s 146,000 acres of training grounds. In fact, it had no precedent in the Army. For the first time, American soldiers had struck a target located and identified by an AI program. Colonel Joseph O’Callaghan, the fire-support coordinator for the 18th and the leader of its AI targeting efforts, keeps a picture of the moment in a conference room, the tank engulfed in a bright fireball. “It showed us the art of the possible,” he says.

A framed picture of the US Army’s first AI-enabled strike. Photographer: Cornell Watson for Bloomberg Businessweek

Less than four years after that milestone, America’s use of AI in warfare is no longer theoretical. In the past several weeks, computer vision algorithms that form part of the US Department of Defense’s flagship AI effort, Project Maven, have located rocket launchers in Yemen and surface vessels in the Red Sea, and helped narrow targets for strikes in Iraq and Syria, according to Schuyler Moore, the chief technology officer of US Central Command. The US isn’t the only country making this leap: Israel’s military has said it’s using AI to make targeting recommendations in Gaza, and Ukraine is employing AI software in its effort to turn back Russia’s invasion.

Navigating AI’s transition from the laboratory into combat is one of the thorniest issues facing military leaders. Advocates for its rapid adoption are convinced that combat will soon take place at a speed faster than the human brain can follow. But technologists fret that the American military’s networks and data aren’t yet good enough to cope; frontline troops are reluctant to entrust their lives to software they aren’t sure works; and ethicists worry about the dystopian prospect of leaving potentially fatal decisions to machines. Meanwhile, some in Congress and hawkish think tanks are pushing the Pentagon to move faster, alarmed that the US could be falling behind China, which has a national strategy to become “the world’s primary AI innovation center” by 2030.

The 18th, a 90,000-soldier rapid reaction force, is the largest operational test bed for Maven, a system built around powerful algorithms intended to identify personnel and equipment on the battlefield. Relying on breakthroughs in machine learning, the system can teach itself to pick out objects based on training data and user feedback. The Pentagon’s AI models can also learn whether changes to objects are likely to be significant—suggesting, for example, that an adversary is building a new military facility. All this is fused with information such as satellite imagery and geolocation data from communications intercepts on a single computer interface, called Maven Smart System.

A growing number of US military officers predict that AI will transform the way America and its enemies make war, ranking it alongside the radio and machine gun in its potential to revolutionize combat. The Pentagon, which now has a senior official in charge of so-called algorithmic warfare, asked for more than $3 billion for AI-related activities in its 2024 budget submission. And in a signal of its possible ambitions, the US recently argued at the United Nations that human control of autonomous weapons is not required by international law.

With the US, China and other powers working to incorporate AI into their militaries, the advantage will go “to those who no longer see the world like humans,” Army research officials Thom Hawkins and Alexander Kott wrote in 2022. “We can now be targeted by something relentless, a thing that does not sleep.”

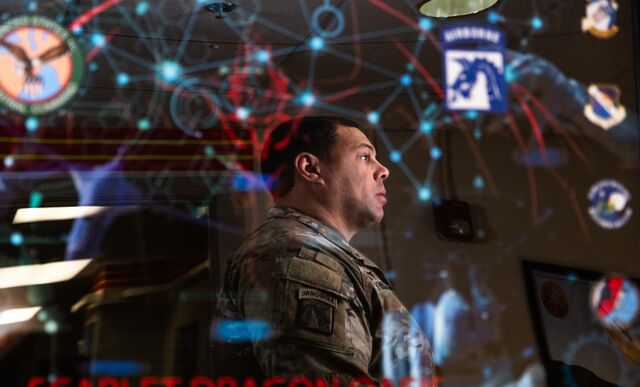

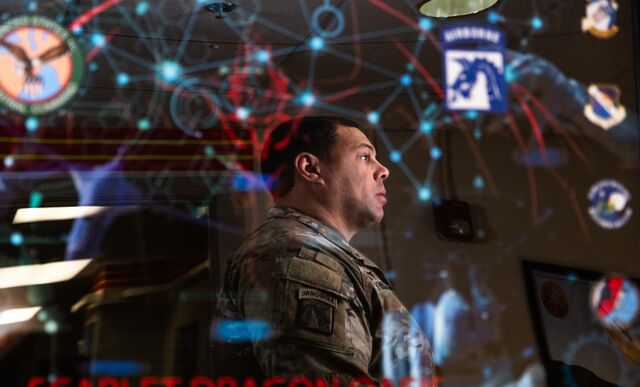

Colonel Joseph O’Callaghan at 18th Airborne Corps headquarters in Fort Liberty. Photographer: Cornell Watson for Bloomberg Businessweek

AI, or something like it, has a long history in the Defense Department. During the Cold War, the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment air-defense system used early algorithms to process radar data. In Operation Desert Storm, an analysis tool helped plan troop movements.

By the mid-2000s, the cutting edge of the field was firmly in the civilian world. Computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton pioneered deep learning, describing in 2006 how machines could teach themselves to identify objects by mimicking the neural networks of the brain. Six years later, he and colleagues revealed that they’d trained a model to classify 1.2 million images with relatively few errors, using an algorithm that attempted to approximate human discernment. The innovations that would ultimately lead to today’s AI tools, such as ChatGPT, were well underway.

As these developments accelerated, Will Roper, a former assistant secretary of the US Air Force who was running a Pentagon office dedicated to advanced technology, watched with increasing alarm. He says that, in 2016, the Defense Department lacked mass cloud storage or computer-friendly data, and officials had a poor understanding of machine learning.

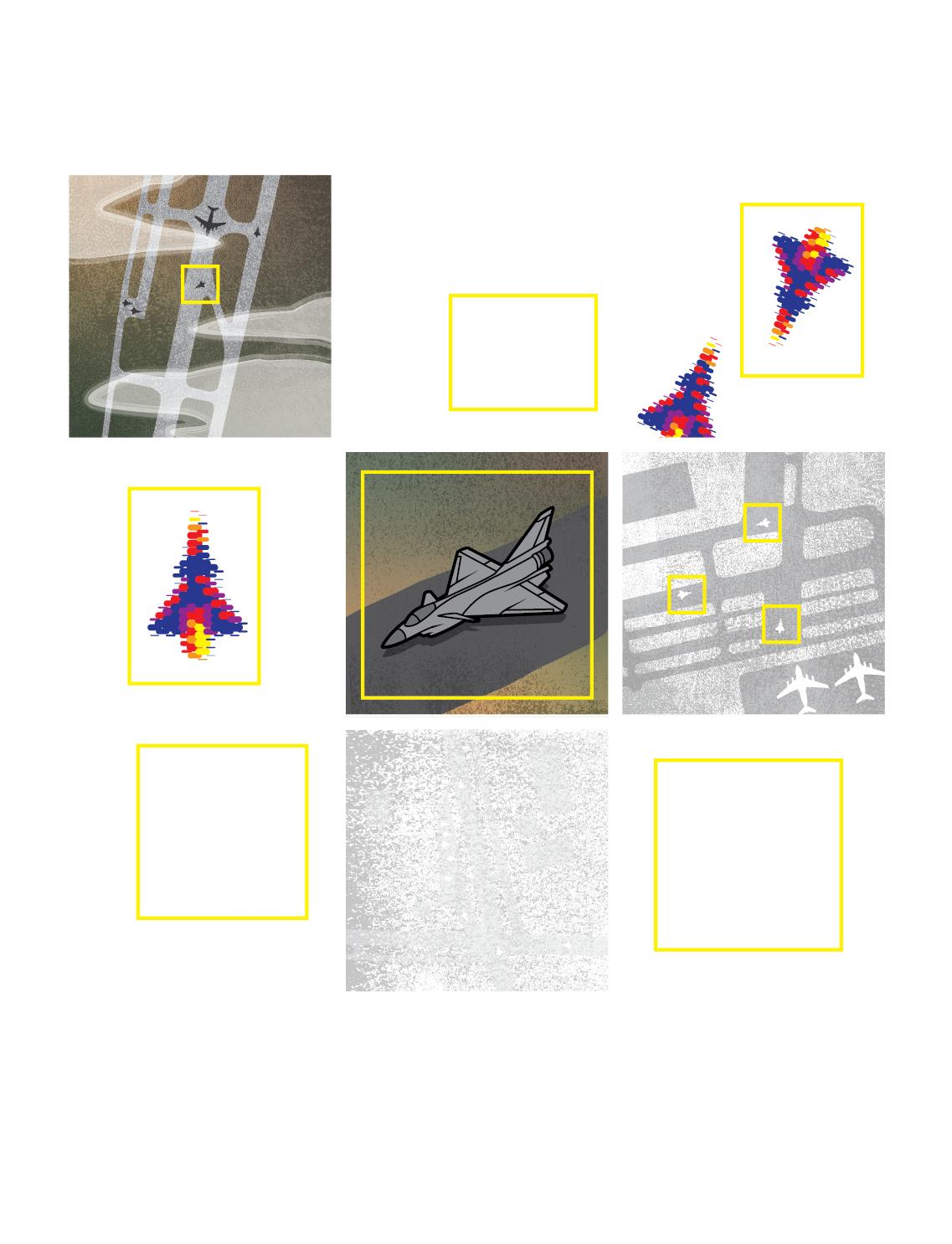

Concerned that the military would be unable to develop its own tools in a reasonable time frame—major US weapons systems can take 15 to 20 years to become fully operational—Roper proposed a single, $50 million program to apply machine learning to automatic target recognition. Traditionally, identifying and classifying an enemy’s assets on the battlefield was a laborious process. Analysts might spend hours or days combing through satellite images and surveillance data, mostly relying on their own eyes. Although other automatic targeting software existed, soldiers viewed it as too slow and too prone to making incorrect judgments.

In 2017 a broader version of Roper’s idea came into being under the Defense Department’s intelligence directorate as Project Maven—more officially, the Algorithmic Warfare Cross-Functional Team. The Maven group set out to assess object recognition tools from different vendors, testing them on drone footage recorded by US Navy SEAL units in Somalia. None performed particularly well, recalls Jane Pinelis, who oversaw the early testing and evaluation of algorithmic warfare at Maven. (She now leads an engineering group at Johns Hopkins University.) The source images were often too hazy, or shot from angles that confused the algorithms, or so poorly labeled that it was hard to train the models. The vendors’ programs were also inconsistent. One might flag an object simply as a tank, another as a Soviet-designed T-72. Performance was even worse outside the lab, where the systems struggled to handle poor network connections and old computers, both common problems in the field.

Other issues emerged as Maven grew. In 2018 thousands of engineers at Google, one of the Pentagon’s original partners, signed a letter protesting the company’s involvement in “warfare technology.” Google didn’t renew its contract. Later that year the Pentagon formally exempted Maven from public disclosure, arguing that information about its capabilities—and limitations—was so sensitive that releasing it could give an edge to America’s enemies.

Chief Warrant Officer 4 Joey Temple. Photographer: Cornell Watson for Bloomberg Businessweek

Despite Google’s exit, a wide range of other technology and defense players remained involved with Maven, and others have since joined. According to people familiar with the program, who asked not to be identified discussing nonpublic information, the main data-fusion platform that underpins the system is made by Palantir Technologies; Amazon Web Services, ECS Federal, L3Harris Technologies, Maxar Technologies, Microsoft and Sierra Nevada are also among a dozen main contributors. All either declined to comment for this story or did not respond to requests for comment.

Gradually, Maven improved, and in 2020 O’Callaghan’s then-commander at the 18th asked him to investigate how useful it could be in weapon strikes. O’Callaghan started using it in a growing number of live-fire exercises, including the 2020 artillery test at Fort Liberty. In collaboration with other US services and allies such as the UK, the 18th has since used Maven and weapons systems connected to it to strike targets from bombers, fighter jets and drones, and modeled how to do so from submarines. “We’ll find it, and we’ll strike it,” O’Callaghan says. A competitive cyclist, he likens improving AI systems to eking out faster race times through tiny changes to training and technique. In one such effort, he recruited local college students to label more than 4 million images of military objects such as warships, helping to train Maven algorithms.

A keepsake in Temple’s office. Photographer: Cornell Watson for Bloomberg Businessweek

But among the soldiers, sailors and airmen who’d have to use the system, skepticism was common. In July 2021, when a Palantir representative offered to demo Maven for Joey Temple, who’d just joined the 18th as a senior targeting officer, Temple refused. A father of eight and veteran of five combat tours in Iraq—on a windowsill in his office at Fort Liberty, he keeps a model skull wearing the unit’s maroon beret, a dagger clenched between its teeth—Temple wasn’t about to put his trust in new software. “This s— don’t work,” he recalls thinking. “I was like, ‘I don’t need another freaking targeting thing. I don’t care. I have enough crap to try to manage.’”

A month later, Temple began to change his mind. He was assisting with the evacuation of US forces and their allies from Afghanistan; ultimately, 120,000 people would be airlifted out of Kabul in dangerous conditions. Temple was given access to Maven Smart System to help make sense of the situation. On a single screen, he could combine data feeds that tracked aircraft movements, monitored logistics, watched for threats and showed the locations of key personnel. “I could see General Donahue walking around,” he says, referring to Chris Donahue, who’s now the 18th’s commanding officer and was the last US soldier to leave Afghanistan. So could hundreds of people logged on to the same system from Kabul, the Pentagon and, according to Temple, the White House. “That’s when I became a believer,” he says.

The headquarters of the 18th Airborne Corps at Fort Liberty. Photographer: Cornell Watson for Bloomberg Businessweek

The Maven platform has advanced significantly since its early days. In addition to video imagery, it can now incorporate data from radar systems that see through clouds, darkness and rain, as well as from heat-detecting infrared sensors—allowing it to look for objects of interest such as engines or weapons factories. It can also analyze nonvisual information, by cross-referencing geolocation tags from electronic surveillance and social media feeds, for example. The technology has helped enable computers to occupy four of the six places in the 18th’s “decision-making loop,” a process which can culminate in an order to fire. Software determines what data to gather, collates and analyzes the resulting information and communicates a commander’s decision to act—potentially to a weapon system. It’s up to humans to decide whether to pull the trigger.

Temple estimates that, with Maven’s assistance, he can now sign off on as many as 80 targets in an hour of work, versus 30 without it. He describes the process of concurring with the algorithm’s conclusions in a rapid staccato: “Accept. Accept. Accept.” Trusting the computer entirely would be faster still, but Temple says that would introduce errors. “I don’t ever wanna get caught short,” he says. “We get caught short, we’re screwed.”

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the 18th’s AI engineering efforts took on new urgency. O’Callaghan, Temple and 270 others from the corps headquarters had deployed to a garrison in Germany, taking over a former racquetball hall as a command center. Maven Smart System was open on many of their screens. An information operations and civil affairs officer, who asked not to be named because she often deploys on special operations missions, became one of those using the software to brief Army commanders.

The officer’s focus was on judging whether Ukrainians in particular areas had the will to resist Russian forces. “When you layer things, different things begin to jump out at you,” she says. “I would have pins dropped on every event that was resistance-related on the map.” These ranged from the mundane—sightings of blue and yellow ribbons tied to fence posts—to the violent, such as attacks on Russian officials in occupied zones. These details, along with many others, then made their way into the classified system US commanders use to inform their understanding of events on the ground.

O’Callaghan and Temple declined to detail how the Pentagon is employing AI systems such as Maven to support Ukraine. But people familiar with the operations, who asked not to be named given the subject’s sensitivity, say the US has used satellite intelligence and Maven Smart System to supply the locations of Russian equipment to Ukrainian forces, who have then targeted those assets with GPS-guided missiles. One of the people says that aiding Kyiv has also helped the Pentagon get much better at using AI tools—and more confident in its forecasts of how they might be used in a conflict with China. (During the first 10 months supporting Ukraine, Maven underwent more than 50 rounds of improvement, according to another person with knowledge of its development.)

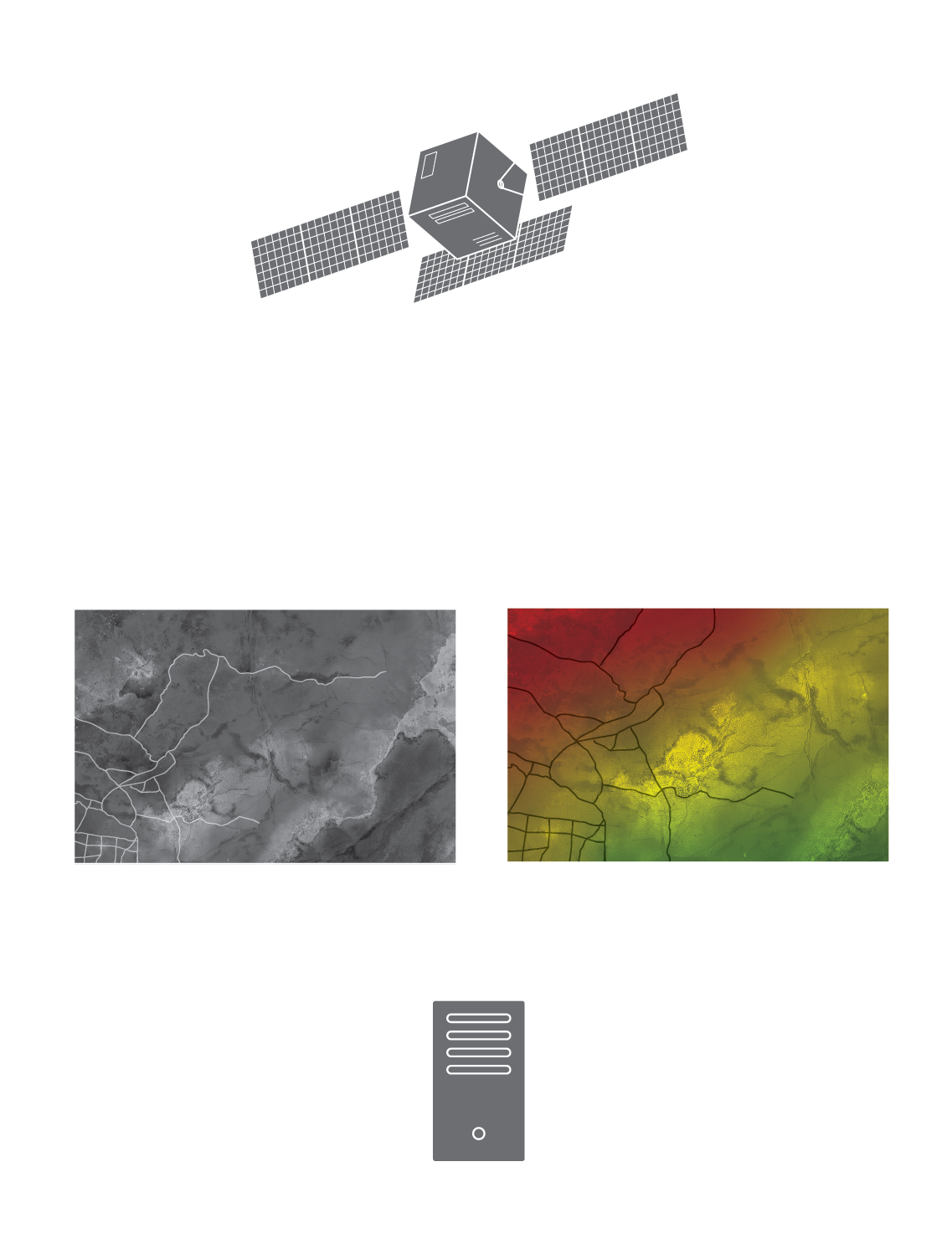

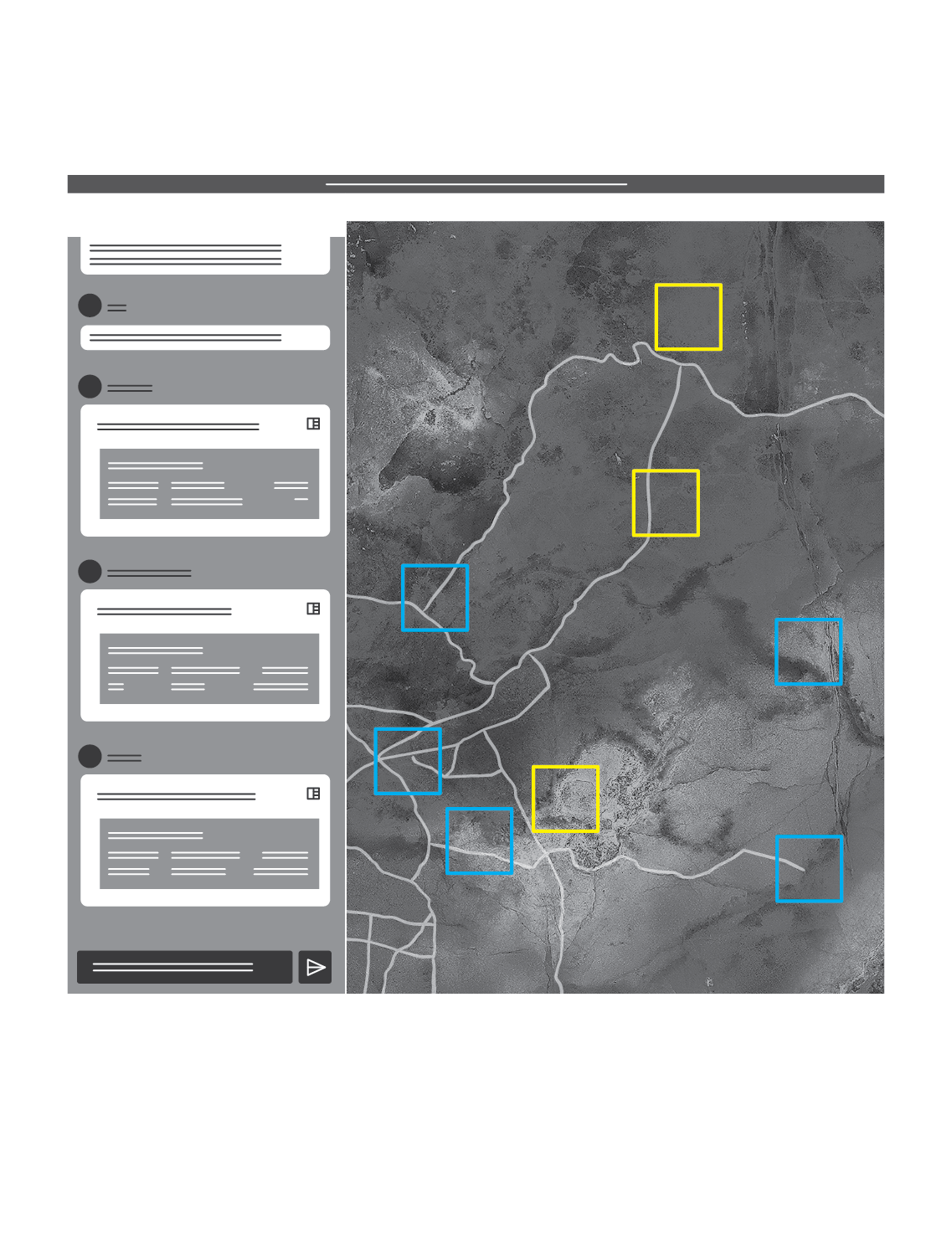

I was given a demonstration of Maven when I visited the 18th last year. It was drawn from a real-life operation in early 2023, when a US Navy ship evacuated American citizens from Sudan, which was in the midst of a civil war. The system’s central map was generated, in the case of my demonstration, from unclassified satellite imagery. On the surface, yellow boundary boxes marked where algorithms had identified ships in the Gulf of Aden. Blue areas signified places that would be included on a no-strike list, such as hospitals and schools. On the left side of the screen, icons offered separate data streams, such as vessel tracking feeds, that could be overlaid on the map. There was also a function for a “tactical data link”: a method for transmitting a commander’s decision to fire a weapon directly between machines.

On the Maven Smart System interface, which brings together multiple data feeds, commanders can view the whole battlefield at a glance. For example, yellow-outlined boxes show potential targets and blue-outlined boxes indicate friendly forces or no-strike zones, like schools or hospitals.

Then officers assess the models to make decisions around potential actions, including weapons fire.

Last year the Pentagon gave primary responsibility for developing Maven to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which specializes in analyzing mapping and imaging. Its director, Vice Admiral Frank “Trey” Whitworth, is a naval officer who formerly served as intelligence chief for SEAL Team Six, the unit that killed Osama bin Laden. The NGA, which has set up a dedicated office at Fort Liberty, is focused on expanding Maven’s data feeds, speed and capabilities, which are then deployed for testing to the 18th and other users in more than a hundred locations around the world. Soldiers’ feedback can then be incorporated into continuous rounds of development. “It’s a perfect marriage,” Whitworth says.

Maven was recently reclassified from a developmental project to a “program of record,” a Pentagon designation that will likely make it easier to secure further funding. According to Whitworth, the platform has made some of its most significant technological strides since the NGA took it over, including improvements to the accuracy of identifications. Whitworth says he “wouldn’t look myself in the mirror” if he wasn’t developing a targeting system that could “cross the finish line.” But he says that humans will always oversee the US military’s AI systems, which will adhere to the laws of armed conflict. Moreover, he says, there are no plans to let machines determine whether to shoot—and kill.

O’Callaghan puts it more colorfully: “It’s not Terminator. The machines aren’t making the decisions, they’re not going to arise and take over the world.”

That doesn’t mean the machines aren’t increasingly important. US Central Command’s Moore says events since Oct. 7, when Hamas launched its surprise assault on Israel, have provided another spur for American forces to accelerate their adoption of AI. They’re now engaged in on-and-off combat across the Middle East. In early February, the US struck more than 85 targets in Iraq and Syria in response to an attack by Iranian-backed militants that killed three Army reservists, and it has repeatedly bombed sites in Yemen. “Maven has become exceptionally critical to our function,” Moore says.

Moore, O’Callaghan and other officials are nonetheless the first to admit that their AI systems have a very long way to go and don’t trump human decision-making. Algorithms honed on desert conditions in the Middle East—for obvious reasons, the source of much of the American military’s real-life data—are far worse at identifying objects elsewhere. Overall, O’Callaghan says, the 18th’s human analysts get it right 84% of the time; for Maven, it’s about 60%. Sometimes the system confuses a truck with a tree or ravine. Tanks are generally the easiest to spot, but with objects such as anti-aircraft artillery, or when snow or other conditions make images harder to parse, the accuracy rate can fall below 30%. In Moore’s view, “the benefit that you get from algorithms is speed,” with recent exercises showing that AI isn’t yet ready to recommend the order of an attack or the best weapon to use.

Other concerns are more fundamental. As the US and its allies come to rely on AI systems, adversaries could attempt to undermine them by poisoning training data or hacking software updates. Algorithms can lose accuracy over time, and because their decision-making is opaque, they’re harder to test than other military technologies. All this means that when it comes to using AI in the field, commanders will have to judge whether military need and the broader context justify the risk of errors. Confusing a wave with a warship is one thing; at worst, that might result in a missile crashing harmlessly into the sea. Using AI targeting on a crowded terrestrial battlefield, with civilians in the vicinity, is another matter entirely.

Despite their limitations, the US has indicated that it intends to expand the autonomy of its algorithmic systems. The Defense Department issued a directive last year instructing commanders and operators to exercise “appropriate levels of human judgment” over the use of force—suggesting officials may see human supervision, rather than initiation of decision-making, as adequate.

To activists who fear the consequences of giving machines the discretion to kill, this is a major red flag. Stop Killer Robots, a coalition of human rights and expert groups, says current US commitments fall “drastically short” of sufficient safeguards. UN Secretary-General António Guterres is leading a group of more than 80 countries that has called for a ban on autonomous weapons systems. “Machines with the power and discretion to take lives without human involvement are morally repugnant and politically unacceptable and should be prohibited,” Guterres said in July.

Not all of the worries come from outside the military. Colonel Tucker “Cinco” Hamilton, an Air Force officer who works on AI testing and operations, outlined an alarming thought experiment at a recent conference. In the scenario he set out, an AI-enabled drone, after receiving an order to call off a mission, decides to kill its operator—having concluded the human was getting in the way of its objective. Hamilton called the prospect “plausible,” though a different Air Force official later described it as “pretty implausible.” Ideas like this remain, for now, the stuff of science fiction, but the trend toward greater autonomy is clear. Just one example: Under an initiative called Replicator, unveiled last year, the Pentagon has asked contractors to develop autonomous, expendable drones it can purchase by the thousands.

In all, the US military has more than 800 active AI projects, with goals that include processing weapons-sensor data and planning resupply routes for ammunition, among many others. The number of separate programs for the Army, Navy and Air Force can be a source of tension. One former senior defense official, who asked not to be identified due to the sensitivity of the topic, says that such fragmentation, and the age-old challenge of breaking down silos among military services and commands, will slow the adoption of algorithmic warfare. Maven isn’t immune to such complaints. To critics, it’s too dominated by the Army, too focused on computer vision and too reliant on one corporate partner, Palantir. Some also complain that it simply doesn’t work well enough.

Vice Admiral Frank “Trey” Whitworth at NGA’s 24/7 operations center. Photographer: Will Martinez for Bloomberg Businessweek

Looming over all these efforts is anxiety about China. US officials worry Beijing could be ahead in technologies such as deep learning and moving to integrate those capabilities into its armed forces. Concern over China’s military use of AI was one reason the White House imposed stricter export controls on high-end computer chips in October. The Pentagon has also added the leading Chinese memory chipmaker and a prominent facial recognition company to a list of firms it says are aiding the People’s Liberation Army.

When it comes to China, US military AI development has two broad aims: to deter a hot war, whether over Taiwan or another flashpoint, and to be ready to fight one should deterrence fail. Last year the 18th began conducting AI targeting exercises with US Indo-Pacific Command, or Indopacom, which is responsible for the Taiwan Strait as well as the contested South China Sea. Maven was also a major component in a separate set of exercises that modeled potential threats in the Indo-Pacific region using AI tools. One goal was to advance a long-running effort to connect sensors, weapons and other systems across all branches of the US military, delivering the information to commanders on one live interface—a single pane of glass to see right through the fog of war.

Still, military commanders are fond of saying that the enemy gets a vote. In a conflict, China would almost certainly attempt to blind or destroy satellites and threaten surveillance aircraft, making it harder to obtain the data that Maven and other AI targeting platforms need to function. Some officers worry that however much the platform improves, its training so far—predominantly on fixed objects such as parked aircraft—may leave it ill-equipped for a war involving supersonic jets and, potentially, even faster missiles. (Whitworth, for his part, says Maven is useful for moving targets.)

One prominent critic of the pace of progress is Roper, the official who helped set Maven up in the first place. “I still think DOD is just not out of the starting blocks,” he says. “We are so unprepared right now.” Roper envisions a world where algorithms are so central to warfare that the US will fly drones into combat expecting them to be shot down, just to gather intelligence along the way. “Battlefields,” he says, “are going to feel like a fight for data.”

Donahue, the commander of the 18th, sees himself as a participant in just such a contest. As a special operations major in Afghanistan, he extensively used the best software then available, which was supposed to trawl through drone footage and recognize enemy facilities. It was an exasperating experience, and Donahue complained repeatedly that the programs weren’t good enough. Despite those frustrations, he’s pushing his forces to develop Maven and other AI platforms faster.

He acknowledges the risks. For one thing, Donahue says, future operators will have to worry constantly that adversaries have poisoned or disrupted their algorithmic systems. But he says the question of whether to adopt them has already been answered. “You will not have a choice. Your adversaries are going to choose for you that you have to do this,” Donahue says. “We’re already on the way of machines will be fighting machines, robots will be fighting robots. It’s already happening.”

Read next: Can AI Unlock the Secrets of the Ancient World?

More On Bloomberg

Eugen Boglaru is an AI aficionado covering the fascinating and rapidly advancing field of Artificial Intelligence. From machine learning breakthroughs to ethical considerations, Eugen provides readers with a deep dive into the world of AI, demystifying complex concepts and exploring the transformative impact of intelligent technologies.